Zika may not be the only virus of its kind that can damage a fetus

Zika virus may not be the black sheep of the family. Infections with either of two related viruses also cause fetal defects in mice, researchers find.

Some scientists have speculated that Zika’s capacity to harm a fetus might be unique among its kind, perhaps due to a recent change in the virus’s genetic material (SN: 10/28/17, p. 9). Others have argued that perhaps this dangerous ability was always there. It just wasn’t until the 2015–2016 epidemic in the Western Hemisphere that enough pregnant women were affected for public health researchers to identify the association with fetal defects (SN: 12/24/16, p. 19).

But new work suggests this capacity is not Zika’s alone. Pregnant mice infected with West Nile or Powassan virus — both flaviviruses, like Zika — also showed fetal harm. Over 40 percent of these infected fetuses died. But among pregnant mice infected with one of two other mosquito-borne viruses unrelated to Zika, all of the fetuses survived, scientists report online January 31 in Science Translational Medicine.

The research underscores that “many viruses, including some similar to Zika, can infect the placenta and the cells of the baby,” says George Saade, an obstetrician-gynecologist and cell biologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. “This list keeps growing and highlights the risks from viruses that we are not very familiar with.”

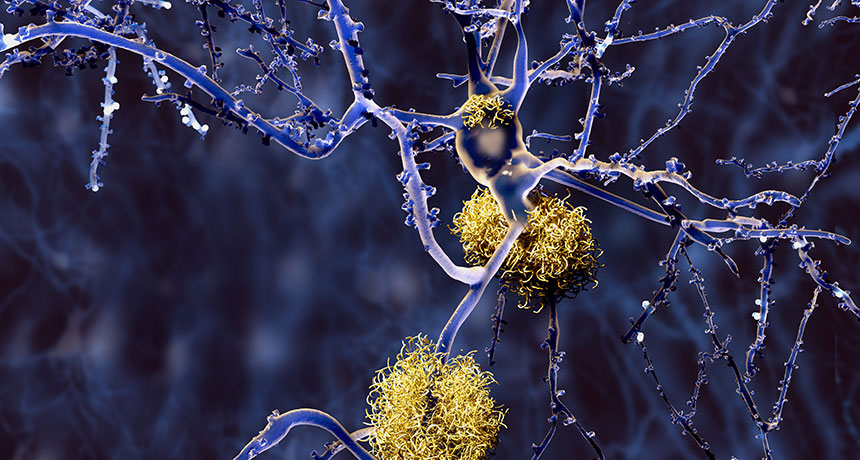

Like Zika, West Nile virus and Powassan virus are neurotropic, meaning these pathogens target nerve cells. Both viruses can cause inflammation of the brain or of the membranes that surround the brain. West Nile is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes that have bitten infected birds. From 1999 to 2016, there were more than 46,000 cases reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Powassan, spread by ticks who have fed on infected rodents, is less widespread; only 98 cases were reported from 2007 to 2016, mostly in the Northeast and Great Lakes area.

Jonathan Miner, a virologist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and his colleagues conducted some of the initial work in mice that demonstrated that Zika could harm fetuses (SN: 6/11/16, p. 15). The new study tests the effects of four other viruses: the two flaviviruses and two alphaviruses, chikungunya and Mayaro, which also have led to outbreaks in Zika-affected areas.

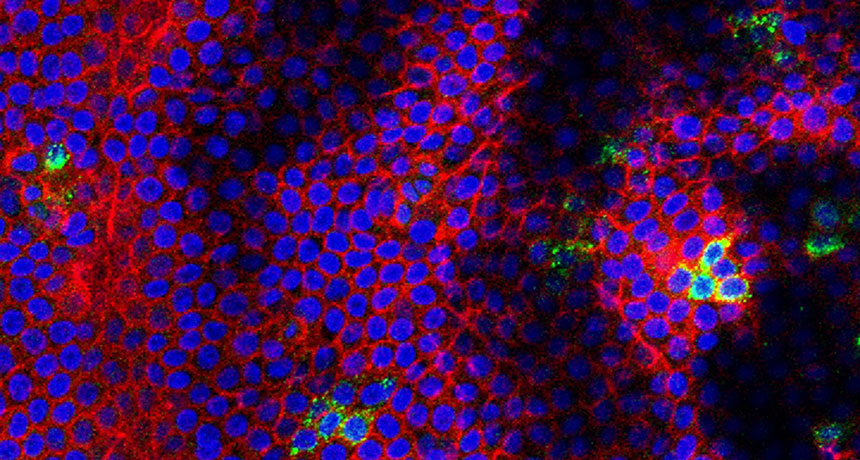

The researchers infected 14 mice early in their pregnancies with one of the four viruses. By late pregnancy, 12 out of 30 fetuses from West Nile–infected mice had died, and half of the 16 fetuses from Powassan-infected mice had died. All of the fetuses from mice infected with chikungunya and Mayaro virus survived. West Nile virus and Powassan virus also replicated, or multiplied, more efficiently than the alphaviruses in lab samples of human placental tissue.

Zika, West Nile and Powassan share similarities in their genetic information, Miner says. “So there may be certain features of those virus genes and proteins in that particular family that confers this ability to infect certain cell types.” But scientists don’t understand fully what those features are yet, he says.

While this is the first study comparing the effects in mice of these mosquito-transmitted and tick-transmitted viruses in parallel, Miner says, past studies have raised the possibility of fetal infections with other flaviviruses besides Zika. A 2006 study of 77 pregnant women infected with West Nile virus reported that two had infants with microcephaly, the birth defect lately associated with Zika that results in unusually small and damaged brains.

In general, examining the potential effects of other flaviviruses on pregnant women and their developing fetuses is difficult, because outbreaks have been sporadic and less widespread than with Zika. It’s possible that cases in humans “could go largely unnoticed if we don’t look for them,” Miner says.