Xi meets Comorian president

Chinese President Xi Jinping on Monday met with Comorian President Azali Assoumani, who is in Beijing for the 2024 Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).

Chinese President Xi Jinping on Monday met with Comorian President Azali Assoumani, who is in Beijing for the 2024 Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).

Editor's Note:

Large models, robots, intelligent manufacturing, autonomous driving… In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has made headlines around the world.

In real life, AI has permeated all aspects of everyday life, helping with scientific research in laboratories, assisting in the restoration of mysterious ancient scrolls at archaeological sites, and helping rescue abducted children in the vast sea of humanity. The development of this technology has also raised a number of ethical and legal challenges. Many experts advocate that humans should see this technology as a tool created for the ultimate purpose of serving humanity, making life and work more efficient and comfortable.

In light of this, the Global Times has launched the "AI empowers industry, improves people's livelihoods" series, showcasing the tremendous energy and broad prospects that AI brings across every aspect of society.

This is the sixth installment in this series. The installment sets its sights on Paris, where global top athletes are vying for medals or personal bests. Behind Team China is the growing technological force, which helps them fight to win more scientifically and efficiently with AI tech. In China, the rapidly progressing AI not only plays a crucial role in high-level competitive sports, but also contributes significantly to the development of mass sports, and the popularization of sports culture.

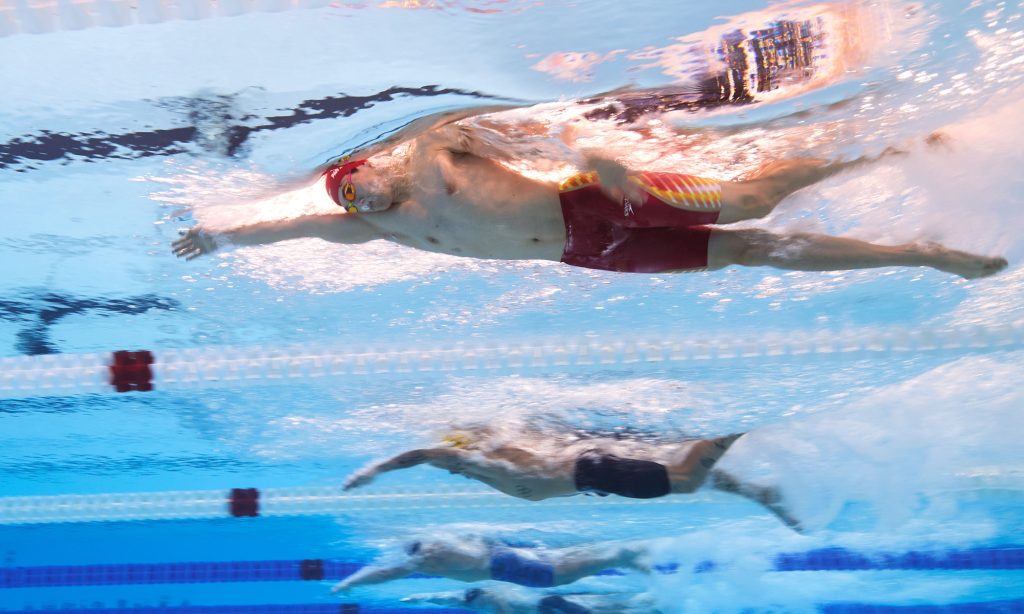

Having jumped off the starting block and plunged into the water, Chinese swimmer Pan Zhanle, at La Défense Arena in Paris, won an Olympic gold medal in the men's 100m freestyle on Wednesday local time, breaking the world record amidst loud cheers.

This particular night echoed the past several months, when the Chinese swimmer and his teammates leaped into the water countless times during training sessions back home. At that time, their coaches and technical staffers gathered by the poolside around a screen, which displayed the complete process of a swimmer's start from the block and underwater movements, with data like the swimmer's entry distance and angle.

"Cameron van der Burgh (South African men's 100m breaststroke Olympic champion) made an entry angle of 37 degrees, which we can use as a reference." Fixating on the screen, they discussed the details of the swimmers' movements, probably for the umpteenth time.

They trained with the help of "SUS large sport model," China's first-ever large model designed for professional sports. Team China at the ongoing Paris Olympics is largely benefiting from AI, as the rapidly developing technology is widely used in China's various fields including competitive sports.

The very front line

Jointly developed by the Shanghai University of Sport (SUS) and a Chinese tech company, the SUS large sport model and its related technologies have been serving the daily training and Paris Olympic preparation of China's several national teams, such as diving, swimming, track and field, gymnastics, and rock climbing, according to Li Yongming, a SUS professor and member of the large model team.

With its vertical models that can study global sports literature data and automatically analyze videos and images from sports training and matches, the SUS large sport model assists athletes to better review and understand their performances with quantifiable metrics, and to make targeted training plans based on the metrics, Li told the Global Times.

As the Olympics unrolls in Paris, busy tech support staff are usually seen in venues apart from traditional personnel like coaches and team doctors. Then how much can AI help China's Olympic athletes striving for gold medal glory?

On Wednesday night local time, China pulled off an amazing 21-15 victory over gold medal favorites Serbia in a men's basketball 3x3 game. When the match ended, some Chinese tech support staff hurried away with videos they just shot during the game.

About one hour later, a detailed analysis with almost all the kinematics data relevant to this game came out. From every move of the players to their physical states, these data will effectively contribute to their post-match summary and preparation for the next match, said Zhang Mingxin, who directs the science and technology support team of the Chinese national basketball 3x3 team at Paris Olympics.

Based on a three-dimensional dynamic capture technology and algorithm, the AI system real-time tracks and analyzes the players' motions and the basketball's trajectories, explained Zhang, who is now in Paris. "Then we can obtain useful data, like a player's real-time load intensity and movement path, and AI-generated professional analyses according to the data," Zhang told the Global Times via phone.

All the dynamic capture process is completed without bothering players in the game, Zhang noted. "Comparing with the previous techs that might require players to wear uncomfortable censoring devices, this system does everything in a contactles way," he said.

Moreover, traditional dynamic capture technologies that depend on wearable censoring devices and GPS (Global Position System) usually have 30 to 40 centimeter margin of error, Zhang said. "But our new system has centimeter-level accuracy, leading the world in this (basketball 3x3) field," he told the Global Times.

This AI system is co-invented by SUS, Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and a domestic tech firm. It can provide detailed data and analysis on a short turnaround time, helping the team better recover, prepare the next match and adjust tactics according to different opponents in tight schedule, said Zhang.

AI dynamic capture tech is also being used in Olympic preparations of some other Chinese national teams, such as archery. Xiu Yu, who is responsible for motion and technology analysis of the archery team, earlier told media that more than 10,000 data are generated for every arrow shot by the athlete.

"After processing and analyzing the data, [the AI system] will form a report for which is passes to team coaches," Xiu told to People's Daily in April.

Customized training based on intelligent analysis of big data are widely used in the training of Chinese athletes, said Chen Xiaoping, a distinguished research fellow from the China Institute of Sport Science affiliated to the General Administration of Sport of China.

"The overall improvement of scientific training level is an important way to improve [athletes'] performance," People's Daily quoted Chen as saying on April 8. "Behind the competition of competitive sports is a showdown of technological strength and proficiency."

Being part of the pageant

Only being a spectator of the Paris Olympics is somewhat outdated for China's younger generation. Instead of passively sitting in front of the TV, some young Chinese prefer to actively get involved in the Olympics, being a part of this global sports pageant in creative ways.

China AIGC (AI-generated content) Industrial Alliance, for instance, holds a themed event during the Olympics, inviting AIGC lovers to create Olympic-related picture, music, video works with generative AI tools. The event has received more than 70 unique submissions, with most of the participators being millennials and Gen Zers, according to the alliance's initiator Ni Kaoming.

Ni shared some of the highlight works they have received, including an interesting AI-generated animated video that tells the magical journey of a panda to the Olympics. "Although there are some limitations on the use of Olympic elements due to copyright concerns, such as the Olympic rings, there are still many high-quality works that well express the Olympic charm and spirit," Ni told the Global Times.

Chinese tech companies are also offering various creative AI products being specifically designed for the Paris Olympics, which have attracted lots of young Chinese users.

Gen Zer Elaine (pseudonym) shared how she enjoys the Olympics in Shanghai through AI tools. While watching a diving match on Wednesday, she interacts with the event with a "virtual diving expert" - an AI agent of renowned former diving Olympic champion Wu Minxia - on her phone. When the event ends, she uploads her profile photo to an AIGC platform, and seconds later she got an AI-generated poster of her "attending" an Olympic diving match as an athlete.

"And before the Olympics began, I had had a virtual tour to Paris last week with the help of an AI large model," she told the Global Times.

AI does benefit the dissemination of the Olympic spirit and sports culture, Ni noted. "With AI technology, people get much closer to the Paris Olympics, its host city and athletes, and thus make them feel more connected with this pageant," he told the Global Times.

Great sporting potential

The AI market in sports industry is expected to grow from $5.93 billion in 2024 to $20.94 billion by 2029, at a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of greater than 28.69 percent, according to data from market research company Mordor Intelligence.

Apart from the high-level competitive sports, mass sports is becoming a broader stage for AI applications in China. From last year, AI robots are gradually used in post-match rehabilitation of public marathon events across the country. The AI robots, as the robot team's director Li Xiaoning told the media in January, are more helpful and efficient than traditional rehabilitation ways of ice water and manual stretching.

The current 1.0 version of the SUS large sport model mainly focuses on competitive sports. Li said it will definitively cover mass sports in later versions, adding in more content that general public are interested in, such as how to exercise to lose weight.

The AI dynamic capture tech being used for the Chinese basketball 3x3 team has many potential application scenarios in mass spots as well, Zhang said.

He gave an example: the system can be changed into an AI coach that assists beginners of a certain sports to modify their incorrect moves.

"Also, AI tech can mark people's sport performances by evaluating their moves, and that may encourage entertaining competitions and interactions among friends," he added. " In general, AI will bring sports lovers more fun while making them more productive."

Chinese diver Xie Siyi retains Olympic title in men's 3m springboard event

Chinese observers on Sunday hailed the significance of a proposal made by China's top diplomat Wang Yi, who underscored the urgent need for intensified regional cooperation to combat the growing threat of cross-border crime, including online gambling and telecom fraud, during a recent informal meeting with foreign ministers from Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand in Chiang Mai. Experts said that Wang's proposal embodies pragmatic cooperation in the region, with China's initiatives and leadership playing a crucial role.

According to the website of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during the meeting on Friday, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang emphasized the importance of security as a fundamental prerequisite for national development.

Wang said the four countries have undertaken a series of collaborative operations against cross-border crime, resulting in the arrest of over 50,000 individuals involved in gambling and fraud activities since last year.

He called for enhanced border controls, securing national boundaries and managing key entry points to prevent illegal crossings. Wang also advocated improved intelligence sharing, continuous joint operations and swift action to apprehend and repatriate criminals who have fled across borders.

A lasting and stable regional environment relies on the sustained handling of specific issues by the countries involved. Through the process of crackdown on cross-border crimes, consensus is reached, common interests are accumulated, and a habit of cooperation is formed. This, in turn, fosters a sense of community among these countries, enabling them to maintain long-term stability and sustainable development through collaborative efforts and a shared community mind-set, Li Haidong, a professor at the China Foreign Affairs University, told the Global Times on Sunday.

Therefore, China's initiatives and leadership are not only pragmatic but also strategically oriented toward the long term goal, Li noted.

The Ninth Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) Foreign Ministers' Meeting was also held in Chiang Mai, Thailand on Friday, after which the heads of delegations from the six Lancang-Mekong countries issued a joint statement that stressed on jointly combating cross-border crimes, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

Cross-border crime not only damages the international image of the region and the countries involved, but also disrupts the development environment both within and beyond the region, Chinese observers pointed out.

China's initiative aligns with the practical needs and long-term interests of these countries, and this is why it is crucial for all parties to join forces in addressing this urgent issue, they said, noting that it reflects the significant impact that the spillover of issues like drug trafficking and smuggling from within the region has on both the region and the world, Chinese observers noted.

Addressing these problems requires international cooperation, which is why China's proposal is timely and necessary, aiming to protect each country's aspirations for stability, prosperity and development, observers said.

Chinese Foreign Ministry on Thursday lodged serious protests with the Japanese side after Japanese leaders and lawmakers visited and sent offerings to the notorious war-linked Yasukuni Shrine on Thursday as the country marked the 79th anniversary of Japan's surrender in World War II.

Lin Jian, a spokesperson for the ministry urged Japan to stay prudent on historical issues such as the issue of the Yasukuni Shrine and make a clean break with militarism.

According to the Kyodo news, during a memorial ceremony Thursday, Emperor Naruhito expressed his "deep remorse," while Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida did not mention Japan's wartime aggression in Asia in his speech.

Despite Kishida not visiting the notorious shrine in person, he sent a ritual offering to the notorious Yasukuni Shrine on Thursday, a symbol of Japan's past brutal militarism, for three consecutive years.

Several ministers visited the shrine, including the hawkish economic security minister Sanae Takaichi, defense minister Minoru Kihara and economic revitalization minister Yoshitaka Shindo. Some LDP lawmakers, including former environment minister Shinjiro Koizumi and former economic security minister Takayuki Kobayashi, also visited the shrine.

According to Kyodo, Takaichi, Koizumi, Kobayashi are considered potential candidates in the forthcoming LDP leadership race after Kishida's recent announcement that he plans to step down.

The Yasukuni Shrine honors 14 convicted Class-A Japanese war criminals from World War II. Visits and ritual offerings made by Japanese officials to the controversial shrine have consistently sparked criticism and hurt the feelings of the people of China, South Korea and other countries brutalized by Japan during the war.

Lin said that the Yasukuni Shrine, where World War II Class-A war criminals are honored, is a spiritual tool and symbol of the wars of aggression waged by Japanese militarists. What some Japanese political leaders did on the issue of the Yasukuni Shrine once again reveals an erroneous attitude toward historical issues.

Facing up to and deeply reflecting on the history of aggression is an essential prerequisite for Japan to establish and develop friendship and cooperation with its Asian neighbors after World War II, Lin said.

"Japanese politicians seem to be in a race to see who is more extreme and right-wing," said Lü Chao, the director of the Institute of US and East Asian Studies at Liaoning University, "their visits of Yasukuni Shrine are a collective publicity stunt to gain political interests."

But for the international community, Yasukuni Shrine visit is a provocation against Japan's taboo of or the Pacifist Constitution and the international order established after World War II, Lü said, "It is also a provocation of denying the history against countries which have been invaded by Japan."

China on Thursday marked the 79th anniversary of Japan's surrender with patriotic events at multiple sites including the Memorial Hall of the Victims in the Nanjing Massacre by Japanese invaders. China's state-run media have also released commemorative posters on social media, saying that China will not forget the suffering and sacrifice of martyrs in resisting invaders.

The South Korean foreign ministry on Thursday expressed "deep disappointment and regret" over the fact that responsible leaders of Japan once again sent offering to and paid respect at the Yasukuni Shrine, and urged Japanese leaders to squarely face history and demonstrate through action their humble reflection and sincere remorse.

Japan's negative and erroneous perceptions of its aggression and colonial history are deep rooted, and the country has not completed a thorough severing of its past militarism, Xiang Haoyu, a research fellow from the China Institute of International Studies, told the Global Times on Thursday.

Japan's biggest problem is that right-wing politicians are trying to win popular support for breaking the Pacifist Constitutional taboo and expanding the military by stirring up so-called threats from neighboring countries and creating geopolitical confrontations in Asia with the US, Xiang stated.

Japan is embarking on a dangerous path of radicalization, which should arouse great vigilance of the international community, especially Asian countries that have suffered from the brutal aggression of Japanese militarism, Lü said.

Ahead of Japan's surrender anniversary, Hideo Shimizu, a former member of Unit 731, the notorious Japanese germ-warfare detachment during World War II, identified the crimes of the Japanese army on Tuesday at the site where he served 79 years ago in Northeast China's Harbin.

Citing sources, Kyodo said on August 10 that a cross-party group of Japanese lawmakers is planning a visit to China in late August. Led by Toshihiro Nikai, a House of Representatives member and a heavyweight in the ruling LDP, the group is dedicated to promoting friendly China-Japanese relations.

On historical issues, China has always kept the Japanese militarists who waged the war of aggression separate from the ordinary people, and has been making positive efforts to safeguard the overall China-Japan relations and the friendship between the two peoples, Xiang said.

Fundamentally speaking, the future of China-Japan relations depends on whether the Japanese politicians could re-establish a correct, objective and comprehensive perception of China, and pursue a positive policy towards China, rather than a one-sided negative rendering of the "China's threat," Xiang noted.

After it was marred by technical glitches, the interview between former president Donald Trump and Tesla CEO Elon Musk on his X platform took place on Monday evening US time. Trump talked at length on some topics, such as the upcoming election, the Ukraine crisis, immigration, climate change and others, while Musk repeated his backing for Trump.

Musk also offered to interview US Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris on his X Spaces platform after his interview with Trump.

The rare public conversation between Trump and Musk, which spanned more than two hours and was overwhelmingly friendly, revealed little new about Trump's plans for a second term. The former president spent much of the discussion focused on his recent assassination attempt, illegal immigration and his plans to cut government regulations, according to the Associated Press.

"If I had not turned my head, I would not be talking to you right now - as much as I like you," Trump told Musk.

Musk said the Republican nominee's toughness, as demonstrated by his reaction to last month's shooting, was critical for national security.

US media NBC News called the interview "largely a Trump monologue." It said that Trump and Musk, born in South Africa, bonded over their shared opposition to immigration, as both said that the US would cease being a real country if immigration continued at current levels.

During their talk, one topic of contention came up between the two - climate change, though Musk called it "global warming." Musk repeatedly advocated for sustainable energy during the chat, while Trump continuously stumped for fossil fuels, claiming instead he's more concerned about "nuclear warming," according to ABC news.

In the hours leading up to Monday's talk, Trump's campaign played it up as "the interview of the century." He also posted a string of campaign videos, attacking Democratic presidential nominee and Vice President Kamala Harris, warning his followers about perceived threats from the political left.

Trump laments the fact that the US doesn't have bullet trains. "We don't have anything like that in our country. It doesn't make sense that we don't," he tells Musk.

In an analysis piece by CNN after the interview, it said that "at times, during their expansive chat, Musk seemed to be using the power of his profile and platform to coach Trump on how to mount a better argument against Harris."

Monday's interview also marked the first major re-appearance of Trump on X since Musk reinstated his account following his purchase of the platform in late 2022.

Al Jazeera said on Tuesday that Trump returned to X as he attempts to recover from a rocky couple of weeks on the campaign trail.

During the interview, Trump then revisited a favored talking point about the amount the EU spends helping Ukraine vs US spending - but rather than promising to cut US aid, he appeared to suggest he wanted the EU to increase its own, according to US media Politico.

"I say, 'why aren't you going to equalize?' Why aren't they paying what we're paying?" Trump told Musk. "Why is the United States paying disproportionately more to defend Europe than Europe? That doesn't make sense. That's unfair, and that is an appropriate thing to address."

Before the interview, European Union Digital Commissioner Thierry Breton wrote an open letter to Musk to remind the latter of his legal obligation to stop the "amplification of harmful content."

"As the relevant content is accessible to EU users and being amplified also in our jurisdiction, we cannot exclude potential spillovers in the EU," Breton said in a statement posted on X.

Breton added that "any negative effect of illegal content" could lead the EU to take further action against X, using "our full toolbox, including by adopting interim measures, should it be warranted to protect EU citizens from harm."

The online event, which was delayed 40 minutes after Musk cited a "DDOS attack" on X's servers, lasted nearly two hours.

XLab, one of the largest cybersecurity company in China, said that using its large-scale threat perception system promptly, it detected the recent attack targeting the X platform.

Gong Yiming, head of the laboratory, said they observed that four Mirai botnet controllers were involved in this attack. Additionally, other attack groups also participated using reflection attacks, HTTP proxy attacks, and other methods.

Monitoring data indicates that the four botnet controllers launched at least 34 waves of DDoS attacks. The four command servers were primarily located in the UK, Germany and Canada. The attack period coincides with the delay in the interview start time, XLab said in its official WeChat account.

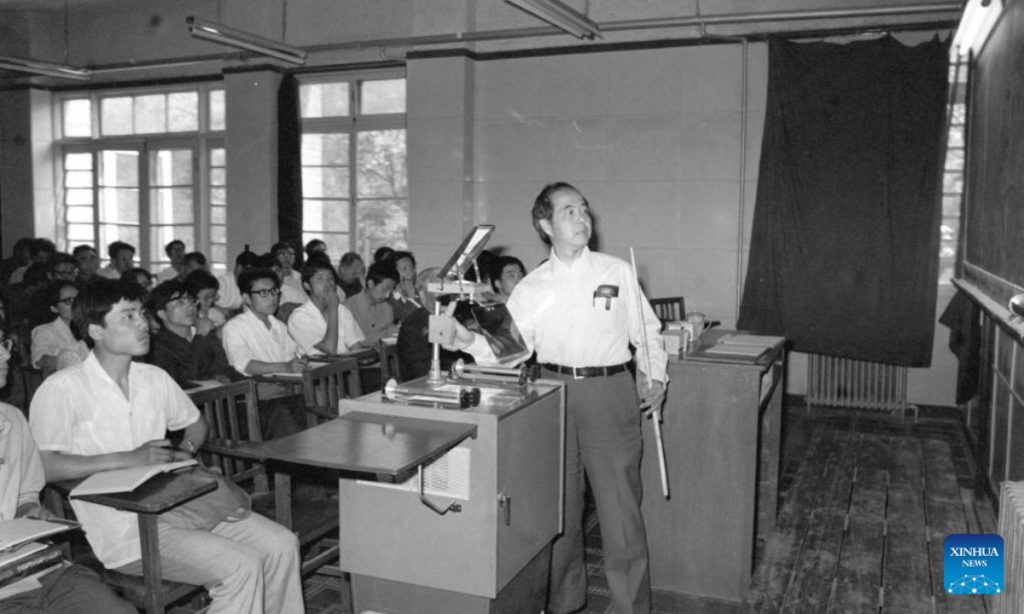

A memorial service was held in Beijing on Sunday to commemorate Tsung-dao Lee, Chinese-born American Nobel Prize winner in Physics and a foreign academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who passed away in the US last Monday at the age of 97, with over 330 attendees expressing deep sorrow fondly recalling Lee's great scientific contributions and endeavor in cultivating Chinese scientific talents.

Renowned as one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century, Lee made significant achievements throughout his more than 60-year academic career, reaching new scientific heights in various fields, such as quantum field theory, fundamental particle theory, nuclear physics, statistical mechanics, fluid mechanics and astrophysics.

Lee cared very much about the development of high-energy physics in China and actively promoted the construction of the Beijing Electron-Positron Collider, the high-energy physics experimental base. He also made great contributions to the advancement of China's science education by initiating and founding the China-US Physics Examination and Application (CUSPEA) program, establishing the Special Class for the Gifted Young at the University of Science and Technology of China. His proposals for the establishment of postdoctoral mobile stations, the founding of the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the China Center of Advanced Science and Technology were also adopted.

On Sunday morning, over 330 people, including Lee's family members, friends, former colleagues, and others from over 30 colleges and scientific research institutes, gathered at the service held at the Institute of High Energy Physics, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Beijing, to fondly recall Lee's scientific contributions and noble character.

Wei Zhixiang, deputy director of the Bureau of Frontier Sciences and Basic Research under the CAS, shared his memories of the scientist and paid deep tribute to Lee on behalf of the CAS.

Wei noted that Lee had always been concerned about and supporting the fundamental research work of the CAS, actively offering suggestions while promoting the leapfrog development of fundamental research talent within the CAS and across the country.

According to Wei, Lee was a fierce advocate of China-US academic activities, playing an active role in establishing related institutions, which laid a solid foundation for international cooperation in fundamental research between China and the US.

Commemorating and remembering Lee means learning from his strategic vision focused on the frontier, his rigorous and scientific academic approach, and his deep and passionate patriotism, Wei said, who advocated intensifying efforts in fundamental research, solidifying the foundation for scientific and technological self-reliance, and producing a series of scientific achievements that will have a milestone impact on the future development of humanity.

Born in Shanghai on November 24, 1926, Lee developed interest in physics at an early age. In 1957, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics with Chen-Ning Yang, another renowned Chinese physicist, for advancing parity nonconservation in weak interactions, overturning what had been considered a fundamental law of nature that particles are always symmetrical.

In addition to his cutting-edge research outcomes, Lee was deeply respected for his efforts in cultivating Chinese science talents and contributing to the development of the study of physics in China by facilitating the establishment of the "Special Class for the Gifted Young," an educational model created at the University of Science and Technology of China and initiating the China-US Physics Examination and Application (CUSPEA) program for selecting the best of Chinese physics students to pursue PhD studies in the US.

Between 1979 and 1989, nearly 1,000 young talents trained in the program have become the key figures in various fields including physics, chemistry, biology, information technology, finance, and economics of the Chinese society, the Global Times learned at the memorial service on Sunday.

Zhou Shangui, director of the Institute of Theoretical Physics under the CAS, expressed profound grief and deep remembrance to Lee on behalf of the institute for Lee's great contributions to the development of China's science and technology, education and talent cultivation in response to the nation's needs and the global scientific frontier.

"The best way to commemorate Lee is through inheritance," Zhou said, "We will inherit and promote the scientific spirit and patriotic dedication of Lee, daring to innovate to meet major needs of the country and making greater contributions to the development of our country's technology and education industry and talent cultivation."

Wang Yifang, director of the Institute of High Energy Physics under the CAS, referred to Lee as an esteemed scientist, a great educator, and a patriot who led China's high-energy physics endeavors to the international forefront.

Lee also played a crucial role in cultivating a large number of young talents for the development of basic research and applied science in China, Wang noted.

New-energy vehicles (NEVs) accounted for 43.8 percent of China's total sales of new cars in July. Sales and exports of NEVs continued to rise, the latest industry statistics showed, showcasing the growth potential of the NEV sector.

In July, NEV production stood at 984,000 units, up 22.3 percent year-on-year, while sales of NEVs totaled 991,000 units, up 27 percent on a yearly basis, according to data released on Friday by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM).

The sales of many NEV enterprises increased significantly in July. For example, the sales of BYD, Li Auto, Leapmotor, Zeekr and Voyah increased by more than 30 percent year-on-year.

According to statistics released by the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) on Thursday, the domestic monthly retail penetration rate of NEVs reached 51.1 percent in July, which means that in China, the majority of consumers opted for NEVs when purchasing passenger cars.

"The main growth driver of the NEV market this year is still plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. This model can be powered by both fuel and electricity, so it has more usage scenarios than other models," Chen Shihua, deputy secretary-general of the CAAM, said on Friday during a briefing on the automobile market in July.

According to a CAAM report published in July, China's annual sales of NEVs are expected to reach 11.5 million in 2024, which would be a record-breaking number.

"China's NEV sector is expected to maintain a stable growth trajectory in the coming months, thanks to its ongoing technological innovation and upgrades in domestic auto products," Wu Shuocheng, a veteran automobile industry analyst, told the Global Times.

Apart from domestic sales, NEV exports witnessed growth of 1.3 percent year-on-year in July, reaching 92,000 units, CPCA data showed.

China's overall auto exports also saw an annual increase of 19.6 percent in July, according to CAAM data.

The exports have maintained robust growth this year. From January to July, the total exports of cars reached 3.262 million, up 28.8 percent year-on-year.

In the first seven months, China's NEV exports surged 17.8 percent year-on-year, CPCA data showed.

US PC maker HP on Thursday refuted foreign media reports alleging the company was relocating half of its personal computer production away from China, emphasizing the company is committed to Chinese market operations.

"We remain committed to China and our China operations, and the important role they play in our global supply chain. As part of our standard operating procedures, we regularly engage in scenario planning, exploring various options to ensure we are enhancing the agility and resiliency of our global supply chain to meet the evolving needs of our customers," HP China told the Global Times on Thursday.

The remarks came after Japan's Nikkei Asia reported that HP is looking to shift more than half of its personal computer production away from China, amid concerns over "geopolitical risks." HP has set "an internal goal of eventually making up to 70 percent of its notebooks outside of China," and is setting up a "backup" design hub in Singapore and "betting big on building a production hub in Thailand," the Nikkei report said, citing sources.

The allegations by Nikkei Asia have been dismissed by HP China as "unfounded."

The US' leading PC maker said that China remains a crucial and integral part of its global supply chain, and the company reaffirmed its steadfast commitment to continuing its operations and growth in the country.

In light of the ongoing discussions about supply chain diversification, HP's stance on its operations in China underscores the country's importance as a strategic market for multinational corporations, analysts said.

HP's PC manufacturing business in China continues to play a significant role in delivering high-quality products and services to the global market, and the company is continuously optimizing its strategies to enhance the resilience of its supply chain and better serve its customers worldwide, the Shanghai-based Jiemian News reported, citing the company's statement.

HP is the world's second largest PC maker, trailing only Lenovo.

HP's PC shipments in 2023 totaled around 52 million units, making the company one of the leading players in the industry, the Research firm IDC said. Despite the speculation surrounding a potential production shift, HP's presence in China remains significant, with the country serving as a key supply hub for the company's global operations.

According to a report from guancha.com, the company and its suppliers have built an extensive supply chain network in China, with Southwest China's Chongqing Municipality emerging as the leading global hub for PC exports.

The Chinese government has expressed firm commitment to fostering a business-friendly environment, welcoming investment by global businesses.

China has become a synonym of the best investment destination, and that the "next China" is still China, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning said earlier, regarding reports indicating that foreign companies were considering relocating their supply chains away from China.

The reason why China is the place for the global business community lies in the strong resilience, ample potential and strong vitality of Chinese economy, the fundamental national policy of reform and opening-up and the huge Chinese market, Mao said.

China's imports of goods from the US grew by 1.2 percent year-on-yuan in yuan-denominated terms in July, marking the first rebound since February, customs data showed on Wednesday.

Analysts said the figure displays the complementary or win-win nature of the world's two largest economies, calling for the US side to scrap export restrictions on China so as to boost US exports amid rising challenges faced by the US economy.

China's trade with the US reached 2.72 trillion yuan ($379 billion) during the first seven months this year, registering 4.1 percent year-on-year increase.

After months of decline, July saw China's imports from the US hit 106.03 billion yuan, boosting the January-July total trade volume to 683.91 billion yuan, rising 1.2 percent year-on-year, according to data released by the General Administration of Customs on Wednesday.

The figures underscore the robust trade relations between China and the US, despite ongoing challenges in bilateral ties. The growing import and export data reflect the intertwined economic relationship between the two. Analysts believe that, despite the US government's pressure placed on normal trade, business exchanges between the two countries' companies are fostering improvements in economic and trade interactions.

China's trade volume with the US is growing, now hitting near record levels. This growth has shown that, despite tensions in bilateral relations, their trade is recovering and keeps expanding, He Weiwen, a senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, told the Global Times on Wednesday. Nevertheless, He noted that US government's coercive trade practices against China have hindered bilateral cooperation.

Enhancements in non-governmental trade relations have also contributed to the growth in China-US trade. The recent positive interactions between Chinese and American business people signal an improvement in trade relations, Gao Lingyun, an expert from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times on Wednesday.

On July 22, Rajesh Subramaniam, board chair of the US-China Business Council, led a business delegation to China. The delegation's meeting with Chinese officials including Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Vice Premier He Lifeng and Commerce Minister Wang Wentao reaffirmed their commitment to the Chinese market.

From July 27 to August 1, Ren Hongbin, chairman of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, led a delegation of Chinese entrepreneurs to the US. During the meetings, Ren expressed hope that China and the US would be able to further promote bilateral business relations.

China's foreign trade achieved rapid growth in July, with foreign trade expanding by 6.2 percent year-on-year to reach 24.83 trillion yuan ($3.46 trillion) in the first seven months, setting a new record.