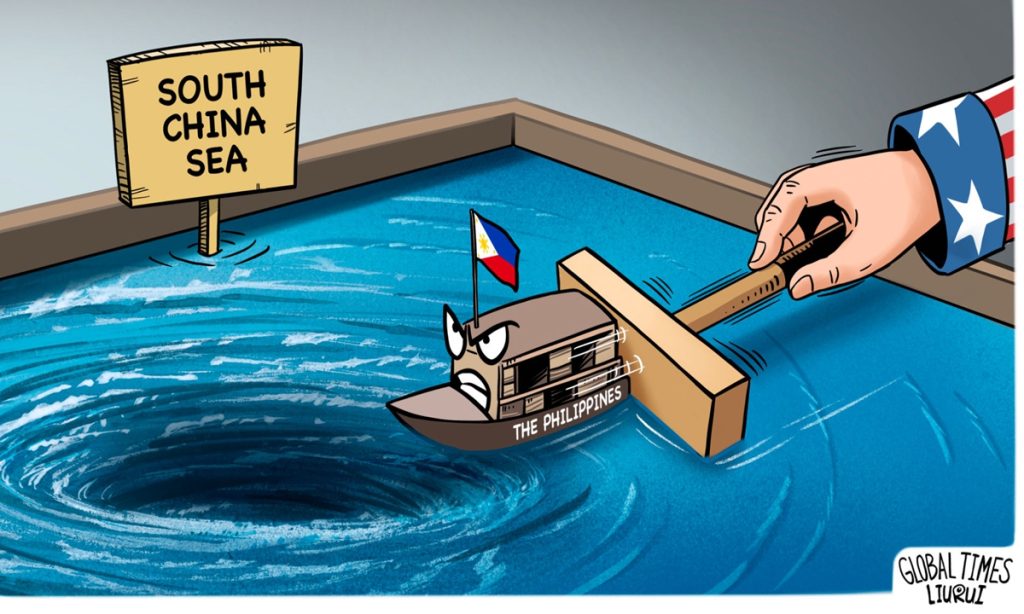

GT investigates: US State Department's support for Manila full of contradictions, serves to further militarize South China Sea

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is set to head to the Philippines on Tuesday to reinforce the American-Philippine alliance through cooperation and security matters, following a recent trade mission there by US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo. This is seen as the latest move in US intervention in the South China Sea issue.

But is the US support for the Philippines really as well-meaning and valuable as it appears? The answer may disappoint many Filipino politicians.

The US' cliché statements act more as a "betrayal of its ally," as it hyperbolizes the Philippines' illegally grounded military vessel at Ren'ai Jiao (also known as the Ren'ai Reef) in South China Sea as a "longstanding outpost," leading to further militarization of the South China Sea and adding fuel to the already tense situation in the region.

Nevertheless, many Filipino officials still see the US' empty promises as a lifeline, exposing their political naivety, analysts said.

This investigative piece will expose the logical flaws, contradictions, danger signals, and perfunctory attitudes replete in the US' statements. Some have even been described by Chinese analysts as "stupid and counterproductive" in relation to Philippine interests and will be an indelible and ugly historical record in US maritime legal practice.

Unprecedentedly malevolence

In its recent statements issued in October and December 2023, and March this year, the US State Department employed a surprising characterization - a "longstanding outpost" - to describe a military vessel that the Philippines illegally "grounded" at Ren'ai Jiao 25 years ago.

"Such a description is extremely symbolic because this is equivalent to making a dangerous characterization of the nature of this territory," said Yang Xiao, deputy director of the Institute of Maritime Strategy Studies at China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. "It has explicitly exposed the US' malevolence in its attempt to undermine peace in the South China Sea region."

The first time that the term "longstanding outpost" appeared was in an October 2023 statement, which said: "Obstructing supply lines to this longstanding outpost and interfering with lawful Philippine maritime operations undermines regional stability." The whole sentence reappeared in another statement in December 2023. The latest statement in March reads: "We condemn the PRC's repeated obstruction of [the] Philippine vessels' exercise of high seas freedom of navigation and its disruption of supply lines to this longstanding outpost."

"Outpost" is a military term that typically refers to a small military base or settlement located in a remote or strategic location. ChatGPT gave some examples of how US media sources have used the word in their news stories, such as "US Military Outpost in Syria Attacked by Pro-Assad Forces (The New York Times)," "US Troops Evacuate Outpost in Iraq amid Rising Tensions (Washington Post)," and "Al Qaeda Fighters Launch Attack on US Outpost in Yemen (Fox News)."

The US has used the word "outpost" only in "anti-terrorism wars" in recent years. "Obviously, building an 'outpost' at Ren'ai Jiao, viewing from the country's state department statement, implies a military action," Yang said.

Therefore, calling the Philippine vessel at Ren'ai Jiao a "longstanding outpost" in defiance of historical facts implies that the US has made clear its support for the Philippines' actions to promote militarization of the South China Sea, Yang told the Global Times.

"I don't know if the US government is aware of the significant implications of their words, or if it was released without careful review. We are truly concerned about the professionalism of US government officials and the standards of their work processes," Yang noted.

The extreme and irresponsible attitude of the US will undermine the current situation of the South China Sea as a sea of peace, friendship and cooperation. It presents a clear opposition to China and ASEAN members' efforts to promote the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, betrays the principles and positions of navigation safety as well as the demilitarization in the South China Sea. It completely exposes who is the true troublemaker in the South China Sea region, according to the expert.

Embarrassingly self-contradictory

Ironically, the description of "longstanding outpost" appears to have put the Philippines in an awkward position.

In the statements, the US has repeatedly claimed its support for "the 2016 arbitration" and called Ren'ai Jiao a "low-tide elevation."

According to the so-called arbitration, some islands and reefs in the South China Sea, including Ren'ai Jiao (known as the Second Thomas Shoal in the West), are low-tide elevations or high tide features that "cannot be appropriated or subjected to sovereignty claims."

Not to mention that the Philippine government has not officially claimed Ren'ai Jiao as its sovereign territory. In a recent story by the Philippine News Agency, Raphael Hermoso, deputy assistant secretary of the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs, called Ren'ai Jiao (Ayungin in the Philippines) "a low-tide elevation within the Philippines' exclusive economic zone and continental shelf." That to some extent reflected the country's "official definition" of Ren'ai Jiao.

Therefore, we can see that US State Department's statements are contradictory in the country's stance over Ren'ai Jiao's sovereignty, Yang said, noting that building military installations out of one's sovereignty is an obvious act of war, which has clearly exposed the Philippines' evil attempts to militarize the South China Sea region.

Observers said that the US statements are apparently putting the Philippines in an embarrassing situation. This also makes the international community see more clearly the US' conspiracy to incite and escalate tensions in the region.

Perfunctory lip service

The US' stance on the Philippines is also extremely perfunctory.

Since the new government of the Philippines took office in May 2022, the US State Department spokesperson has issued nine statements on South China Sea disputes. Eight of them conspicuously bear the same title that reads "US support for the Philippines in the South China Sea."

These statements are repetitive and obsolete, basically focusing on three ungrounded points: Accusing China of not accepting the illegal international arbitration decision issued in July 2016, accusing China of "infringing on the Philippines' freedoms of navigation," and mentioning the 1951 US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty.

Experts say that these statements are very limited in scope. "The US State Department has almost no substantive power in the security cooperation mechanisms with other countries which involves military actions, information assistance, material support, and many other aspects. In the long-term operation of US politics, the actual role of the State Department in foreign affairs is very limited," Yang told the Global Times.

The recently deceased Henry Kissinger, while serving as Nixon's national security advisor, skillfully bypassed the State Department and completed the most shocking diplomatic action since the Cold War - the normalization of US-China relations.

The more crucial support for foreign entities is generally provided by the US National Security Council and the US Department of Defense, including the US Department of Homeland Security. All substantive measures taken by the US must also come from the White House, explained Yang.

"Take the recent example of the statement from US President Joe Biden on Coalition Strikes in Houthi-Controlled Areas in Yemen issued on January 11 as an example. Such actions require long-term international coordination and preparation, multiple rounds of shuttle diplomacy by the Secretary of State, the use of the president's special powers, and subsequent approval from Congress. What's more, even for non-governmental organizations like the Houthi armed forces in Yemen, the US has rallied together with the UK, Australia, Bahrain, Canada, and the Netherlands, and went through a complicated process, not to mention in the South China Sea," Yang said.

In light of this, it is truly ridiculous for a few Filipino politicians to be jubilant, grateful, and verbose to rely on perfunctory verbal support from the US State Department, Yang said.

The contradictory, rough, and provocative statements from the US obviously stand in stark contrast to China's rational and restrained attitude in the South China Sea.

On March 7, 2024, Member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and Foreign Minister Wang Yi once again elaborated on China's position on the issue of the South China Sea when he met the press during the just concluded two sessions.

Wang said that on maritime disputes, China has been exercising a high degree of restraint. China maintains that parties should find solutions that are acceptable to one and all by working in the spirit of good neighborliness and friendship, and on the basis of respecting historical and legal facts. But abusing such good faith should not be allowed. Distorting maritime laws cannot be accepted.

In the face of deliberate infringements, China will take justified actions to defend its rights in accordance with the law. In the face of unwarranted provocation, China will respond with prompt and legitimate countermeasures, said Wang.

China also urges certain countries outside this region not to make provocations, take sides, or stir up trouble in the South China Sea, Wang stressed.